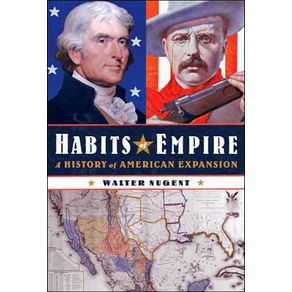

Discussions abound today about the state of the union, its place in the world, and the founding fathers’ intentions. Did they want the United States to become a republic or an empire? Thomas Jefferson, after all, called the young nation an “empire for liberty.” Later words through two centuries all evoked empire: “manifest destiny” in the 1840s, “benevolent assimilation” in 1898, and “our responsibility to lead” in 2002. Indeed, since Jefferson’s day, Americans have proudly proclaimed liberty and cherished democracy even as they have often behaved imperially. Habits of Empire documents this expansionist behavior by examining each of the nation’s territorial acquisitions since the first in 1782—how the land was acquired, how its previous occupants were removed or reduced, and how it was then settled and stabilized. By 1853, when the continental United States was fully established from sea to shining sea, the nation’s habit of empire-building had become firmly formed. Each of the acquisitions is a story in itself. In Paris in 1782, the American negotiators—the crafty Benjamin Franklin, the crabby John Adams, and the crooked John Jay—stubbornly and with much luck pushed the new country’s western boundary to the Mississippi River andalmost gained southern Canada as well. Hardly any Americans yet lived west of the Appalachians, and their armies had not conquered the region, but they won it nevertheless. That allowed Robert Livingston and James Monroe in 1803 to accept Napoleon’sastonishing offer to sell all of Louisiana. Through a volatile mix of leadership, luck, aggression, chicanery, rampant population growth, and self-confident ideology came the further acquisitions of Florida, Texas, Oregon, and the Southwest. From the 1850s through the 1920s, America’s empire-building reached across the Pacific and around the Caribbean. After 1945, American expansion took a new global form, military and economic, and built on the need to contain the Soviet Union in the Cold War.