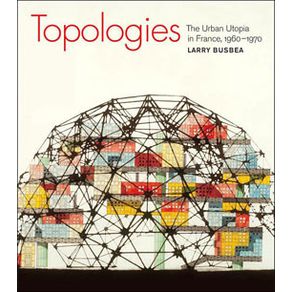

The utopian vision of spatial urbanism - an avant-garde architectural phenomenon that blended technology, leisure, and culture - is examined as a reaction to modernism and official government building and planning in the embattled cultural context of 1960s France. Amid the cultural and political ferment of 1960s France, a group of avant-garde architects, artists, writers, theorists, and critics known as "spatial urbanists" envisioned a series of urban utopias, phantom cities of a possible future. The utopian "spatial" city most often took the form of a massive grid or mesh suspended above the ground, all of its parts (and inhabitants) circulating in a smooth, synchronous rhythm, its streets and buildings constituting a gigantic work of plastic art or interactive machine. In this new urban world, technology and automation were positive forces, providing for material needs as well as time and space for leisure. In this first study of the French avant-garde tendency known as spatial urbanism, Larry Busbea analyzes projects by artists and architects (including the most famous spatial practitioner, Yona Friedman) and explores texts (many of which have never before been translated from the French) by Michel Ragon, the influential founder of the Groupe International d'Architecture Prospective (GIAP), Victor Vasarely, and others. The projects of the Spatial Urbanists were in large part a response to the government's planning policies, its Kafka-esque bureaucracy, and its outdated institutions, which they considered the first obstacles to the implementation of their radical urban designs. But even though the Spatial City was conceived as progressive, by the end of the 1960s some critics had begun to question its ideological foundations.